Are Anti-Science Conspiracy Theories Anti-Pittsburgh?

Columnist Virginia Montanez explores the scientific breakthroughs that Pittsburgh and Pittsburghers have given the world — and explains why the anti-science movement is an insult to our history and achievements.

Not too long ago, I unfollowed an acquaintance on Instagram, when she casually commented that the 1969 moon landing was an elaborate government hoax. Faked. Never happened.

This unfollow wasn’t some rash reaction. I don’t believe that the moon landing occurred because the media (and/or “government propaganda”) told me it happened. Rather, my reaction was planted firmly in science. In primary sources. In reason.

Hell, in being a lifelong space nerd.

I knew too much in the face of my friend, who based belief on far too little. I knew NASA’s Apollo program didn’t land men on the moon just once, but six times. Based on the number of people involved in the program (hundreds of thousands), I knew a study had determined it is essentially a mathematical impossibility that a ruse of that magnitude could be maintained for even the space of five years — let alone five decades. I knew the Soviet Union, our sworn space race enemy, publicly acknowledged our 1969 triumph despite possessing every motivation to deny it.

To me, my acquaintance’s claim was an insult to the humans who dedicated their careers to the science of putting a human on the moon, especially those with Pittsburgh connections. It was an insult to Pittsburgh-born astronaut James B. Irwin, who walked on the moon during the Apollo 15 mission and returned as a deeply religious man who spent the rest of his life publicly connecting his time on the moon to his Christianity. Carnegie Tech graduate Edgar Mitchell might have had something to say to my friend, too; he piloted the lunar module and walked on the moon during the Apollo 14 mission in 1971.

My friend’s claim was an insult to Braddock native and Carnegie Tech grad Alexander Valentine Jr., who mapped potential lunar landing sites for Apollo 11 as part of his work at Raytheon; his team settled on Tranquility Base as one of three ideal spots. It was a slap in the face of Pittsburgh-born Jack Kinzler, the NASA employee whose telescoping cantilevered assembly allowed the planted U.S. flag to appear to “fly” on the moon’s too-thin atmosphere.

Calling it a hoax also is an insult to Pittsburgh companies and the dedicated people they employed. Alcoa provided aluminum for the Saturn V rocket and the lunar lander legs. Westinghouse provided the television camera that recorded man’s first steps and activities on the moon; it’s still up there with Kinzler’s flag and the plaque he designed, too. Mine Safety Appliance provided the respirators used by returning astronauts upon splashdown. The command module was outfitted with relay switches from WABCO.

So it was in their honor, their defense, that I smacked the unfollow button so hard you’d have thought I was trying to angrily and noisily slam a rotary phone receiver in 1983.

But this episode of virtual severance got me thinking — and concluding that much of the anti-science pathogen that is increasingly infecting modern society is a direct insult to Pittsburgh’s rich science history.

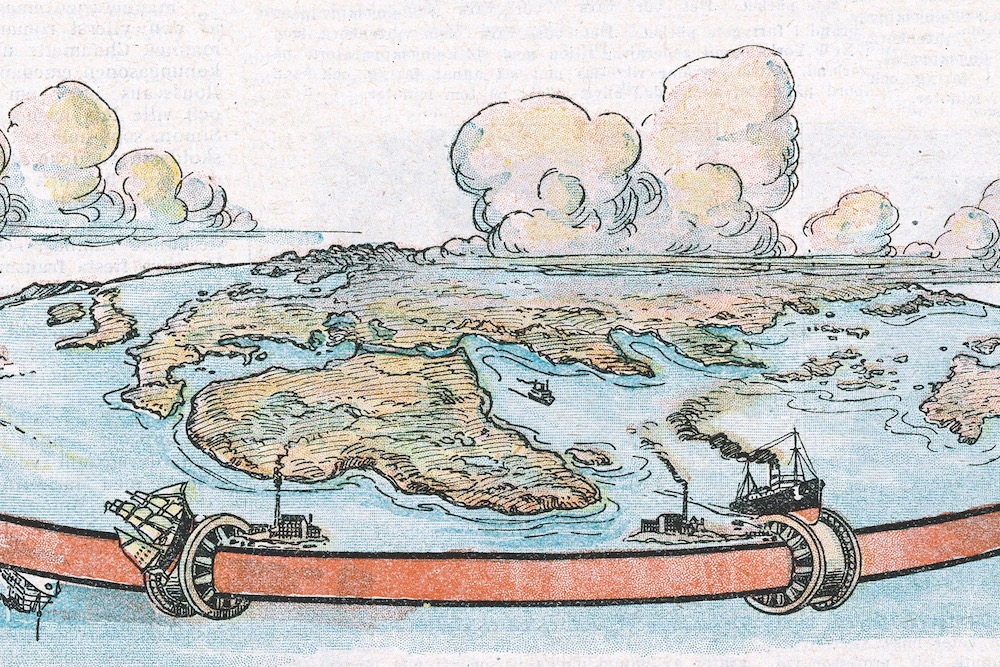

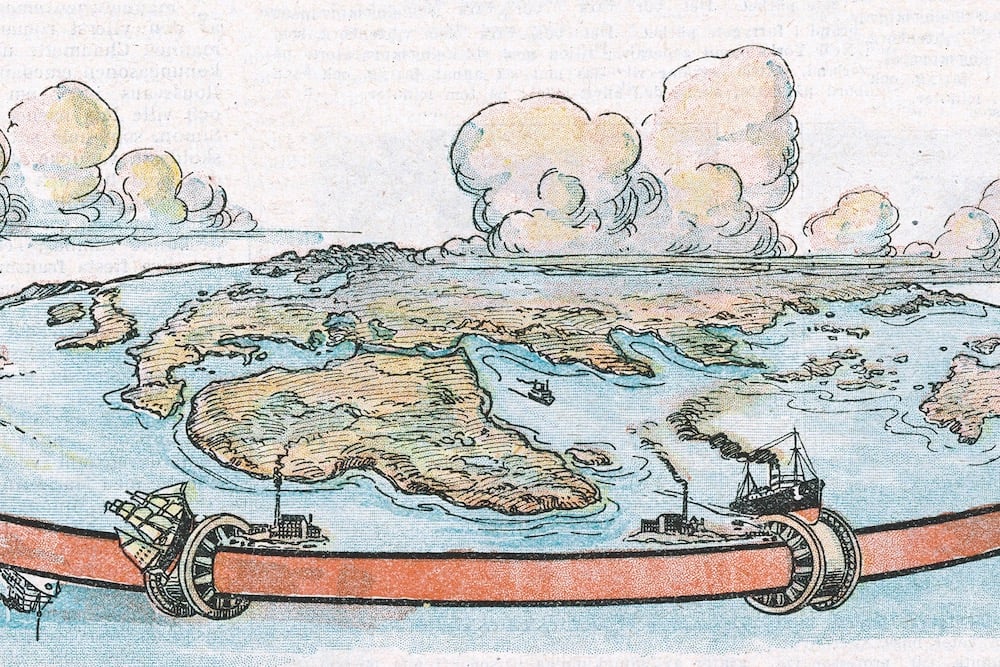

Flat Earthers, the most cringe-inducing faction of science-deniers (simply due to the fact that they don’t understand how gravity works), are doing more than ignoring easily discoverable truths that were plainly evident even to the ancients before man had the tools to see distant planetary spheres. They’re insulting Pittsburgh icons John and Phoebe Brashear who in the 1870s began grinding optic lenses and building increasingly more powerful precision instruments that allowed for the scientific observation of astronomical wonders.

Discoveries made with a Brashear optic formed the early foundation of Albert Einstein’s 1905 theory of special relativity — a theory that launched a transformation of our understanding of the universe and spacetime. It was John Brashear who raised the funds for the construction of our current Allegheny Observatory. Brashear optics and instruments are still scattered around some of the world’s observatories, further advancing astronomical science — none of which refutes the fact that the globe is indeed a globe. The first line of John’s 1925 autobiography reads, “I came into this ‘old round world’ on the twenty-fourth day of November, 1840.”

Round because science — and eyeballs — say so.

Anyone who has bothered to spend even an hour or two engaged in historical research would encounter the intellectually dishonest (and nearly criminal) misinformation and ever-shifting goal posts that provide the foundation for much of the modern anti-vaccine movement — a movement that is a direct affront to the transformative and heroic work of Pittsburgh hero Dr. Jonas Salk (and his team of researchers).

Collectively, we’ve forgotten, or never bothered to learn, of the desperation — the keen, vocal yearning for his vaccine. Terrified parents wondering if this would be the summer the paralysis came for their child’s legs and lungs, or if perhaps this might be the summer the promising work of that virus doctor at the University of Pittsburgh would end the long nightmare.

We’ve forgotten that Salk’s polio vaccine, which led to the disease being declared eradicated in the United States by 1979, was built upon the foundation of his influenza vaccine work. We haven’t read the books, newspaper articles and academic journals that detailed his science, his testing, his failures, his single-minded laser focus on saving children — and his willingness to inject himself and his own children as test subjects. We perhaps didn’t realize, or didn’t bother to learn, that he was his own harshest critic, holding himself to a higher scientific standard than those around him did. We have failed to appreciate that, despite the desperate need for the vaccine, he worked slowly and methodically to ensure safety and efficacy.

Salk’s polio vaccine — declared “safe, effective and potent” on April 12, 1955 — also laid the groundwork for the measles vaccine licensed for use less than a decade later, demonstrating for the field how to create, test and produce safe vaccines for mass public rollout. Measles, one of the most contagious of all the world’s known infections. Measles, right now sickening children and robbing lives with a resurgence catalyzed by falling vaccination rates. Measles, the problem we already solved by eliminating it in 2000 in the United States — thanks, in part, to the work of Jonas Salk.

Science, denied.

Insisting that climate change isn’t real or isn’t caused by human behavior isn’t just closing the mind to tens of thousands of peer-reviewed studies (representing 99.9% of 88,125 studies conducted by 2021), but it’s also an insult to the legacy of a woman we named a bridge after — Rachel Carson. She who dedicated her life to environmental science wrote to a friend more than 75 years ago, “We live in an age of rising seas. Now in our own lifetime we are witnessing a startling alteration of climate.”

It was her book, “Silent Spring,” that launched the environmental movement of the 1960s that eventually led to scientists establishing human-driven climate change as fact, regardless of what anyone’s feelings are telling them.

Insisting the Earth is flat, the moon landing was faked, that vaccines cause autism and that climate change isn’t real or isn’t caused by human behavior is to reveal a mind that is choosing to stay in the darkness when the light of science is there for the taking. More than that, clinging to these false beliefs insults so much of Pittsburgh’s rich history as the home of people who used science to transform lives with the unceasing pursuit of truth.

Jonas Salk once said, “Our greatest responsibility is to be good ancestors.”

Pittsburghers who were dedicated to science left a part of themselves on the moon. Saved countless lives. Discovered the wonders of the universe. Fought on behalf of an Earth that could not fight for itself. They brought honor to our history, our present, our future. They were good ancestors.

Are we?

In her column, Virginia Montanez digs deep into local history to find the forgotten secrets of Pittsburgh. Sign up for her email newsletter at: breathingspace.substack.com.