What’s it Like to Live in a Hotel at College?

Freshmen at both the University of Pittsburgh and Point Park University are having an unusual first year.

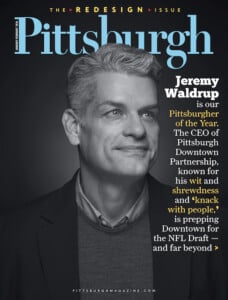

A SHARED ROOM IN THE WYNDHAM GRAND PITTSBURGH HOTEL FOR POINT PARK UNIVERSITY FRESHMEN. IT PROVIDES A FLAT-SCREENED TV ON THE WALL AND A VIEW OF POINT STATE PARK. | PHOTO BY JOHN ARANDA

Vega Mani has become the type of student who shows up to class early. Not by choice — the first-year neuroscience major initially expected to be “running a little late” to her classes. But when your dorm is a 15-minute walk to most classes, and 30 minutes from some, you can’t exactly roll out of bed in the morning.

Mani is one of 250 University of Pittsburgh freshmen placed at the Hampton Inn in West Oakland this fall as the university grapples with its largest incoming class. After receiving a historic 65,000 applications, Pitt found itself with more students than beds, turning to hotels and off-campus apartments to house 400 freshmen.

Similarly, 90 Point Park University students have been placed at Downtown’s Wyndham Grand instead of the regular dormitories.

U.S. colleges and universities experienced a collective 15% drop in enrollment between 2010 and 2021, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. This triggered the closing of several small colleges and the shuttering of departments and layoffs at others. But some institutions like Pitt and Point Park are seeing an uptick — in fact, Pitt welcomed its largest first class ever and Point Park has had its largest first class in years.

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center in spring 2025 tracked a 3.2% increase in overall enrollment compared with the previous spring.

The Pitt Experience

For Pitt students like Mani, the Hampton Inn placement came as “a surprise,” particularly because it hadn’t appeared among her preferred housing choices when filling out the application.

The Hampton Inn “was not my first, second, or third preference. When I filled out my housing application, I put down Nordenberg [Hall], and then Tower A, and then Tower B,” Mani said.

Communication challenges with the university added to her frustration. After receiving an email that her housing assignment was delayed, Mani learned of her Hampton Inn placement. When her family contacted the university seeking alternatives, officials indicated that no other housing remained available.

A SHARED ROOM FOR UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FRESHMEN AT THE HAMPTON INN IN OAKLAND. | PHOTO BY VEGA MANI.

According to university spokesperson Jared Stonesifer, planning for student housing is an ongoing process. The University prepares not only for the next school year, but also for years ahead, guided by The Plan for Pitt 2028. The housing team works with the admissions department to track the number of students who accept their offer, but the final class size isn’t known until after the June 1 deadline. At that time, a concrete number is available to place students in housing.

Pitt selects these locations based on proximity to campus and classrooms, availability of space, and the ability to provide a safe and secure environment for students, Stonesifer said. The university added 400 beds off campus to accommodate the burgeoning freshmen class; in addition to the Hampton Inn, space also was located at the Pennsylvania and Webster apartments on Dithridge Avenue.

At $5,135 per University term, Hampton Inn housing costs $750 more than a traditional double room in Litchfield Towers, which runs $4,385. The price difference reflects the hotel’s amenities and the University’s costs associated with leasing the facility. This adjustment required some families to revise their financial expectations.

“They weren’t very happy about it,” Mani said of her parents’ reaction. “The price of my housing went up for a dorm I didn’t pick.”

Not only has Mani altered her daily routines to accommodate the longer walks to classes, it’s also influenced how she structures her days.

“Since classes have started, I’ve just been on campus the whole day, since it takes too long to walk back and forth from the Hampton,” Mani said. “It’s definitely made me budget my time more.”

The off-campus location also has affected her social life, a crucial aspect of the freshman experience. Mani describes sometimes feeling “isolated” from campus life, particularly the social opportunities centered around traditional residence halls.

“It’s definitely more difficult to meet people and other freshmen because the social scene is in [Litchfield] Towers,” Mani said. “Now that I’ve been on campus a lot, it’s been easier to meet people.”

According to Stonesifer, Pitt residence halls are designed to offer students a safe and supportive living environment. Each hall includes 24/7 security, high-speed Wi-Fi with around-the-clock support, and all utilities. Every building also has a professional Resident Director and a team of Resident Advisors living on site to provide guidance, programming, and day-to-day support to help students navigate their college experience.

Currently, the Hampton Inn lacks its own washer and dryer. Pitt continues to work with laundry and construction vendors to install washers and dryers in the hotel. As a courtesy for the temporary inconvenience, the University has provided free weekly wash, dry, and fold services since the beginning of the semester. Residents have the option to give their clothes to front desk staff for off-site cleaning or to seek alternatives elsewhere on campus.

Mani has found “silver linings” in her Hampton Inn experience. The hotel rooms offer amenities not available in traditional residence halls, including “clean, private bathrooms, refrigerators, televisions and spacious layouts.”

Similar to a traditional Pitt dorm, the building has security guards, requires students to sign in with Panther IDs, and has converted every floor into residential space. Mani says that the primary difference is that “students have to use hotel key cards to open up their rooms.”

“All rising sophomores and juniors with a valid housing guarantee are eligible to enter the housing selection lottery,” Stonesifer said. “Students in overflow housing who wish to live in university-owned housing follow the same process as other Pitt students.”

Pitt’s strategic plan, the Plan for Pitt 2028, sets a goal of enrolling 22,000 undergraduates on the Pittsburgh campus by 2028 — a target the university is on track to meet. To support this growth, Pitt is exploring a range of long-term solutions, including leasing additional space, repurposing existing campus buildings, acquiring new properties and constructing new facilities.

The Point Park Experience

Point Park University, which saw a nearly 20% increase in its 2025 fall freshman class, also turned to hotel housing, partnering with Downtown’s Wyndham Grand next to Point State Park to accommodate 90 students across 45 reserved rooms as the university faced similar enrollment pressures.

The arrangement places students a 5-to-10-minute walk from campus, where they receive access to amenities typically unavailable in traditional residence halls: pool and hot tub facilities, a fitness center, private bathrooms and significantly larger living spaces. The university provided additional furnishings, including clothing racks and foldable dressers, to enhance storage capacity in the hotel rooms.

Keith Paylo, dean of students at Point Park, believes parents will have difficulty convincing their children to leave when summer returns because the accommodations are superior to standard dormitories. The Wyndham, he said, “welcomed them with open arms.”

ANOTHER VIEW OF A SHARED HOTEL ROOM AT THE WYNDHAM GRAND BY POINT PARK UNIVERSITY FRESHMEN. | PHOTO BY JOHN ARANDA

The hotel’s floor layout distributes students across three residential clusters on three floors, supervised by two resident educators — Point Park’s version of resident assistants. Security measures mirror those of traditional campus housing, according to Paylo, with 24/7 monitoring coordinated between hotel staff and campus police.

Resident educator Lindsay Simmons compared the hotel accommodations to on-campus alternatives, where students face a trade-off between Thayer Hall’s communal bathrooms with air-conditioning and Lawrence Hall’s private bathrooms without air-conditioning.

“At the hotel you get the best of both worlds,” Simmons says.

Similar to the Hampton Inn, laundry services have presented the largest challenge for Point Park students. The university arranged a partnership with a commercial laundry service and provided each student’s first $10 bag, but subsequent cleaning costs $2 per pound — potentially reaching $40 for larger loads — became expensive.

Most students found it more practical to transport their laundry to campus facilities rather than pay the ongoing fees, according to Simmons.

The off-campus location has also affected the traditional freshman social experience, like being able to “roam the halls and see what doors are open to visit.”

Point Park selected hotel residents based solely on housing application timing to ensure an unbiased process, according to Paylo. To better to promote community building within the unconventional housing situation, a student lounge has been created for the students at the Wyndham.