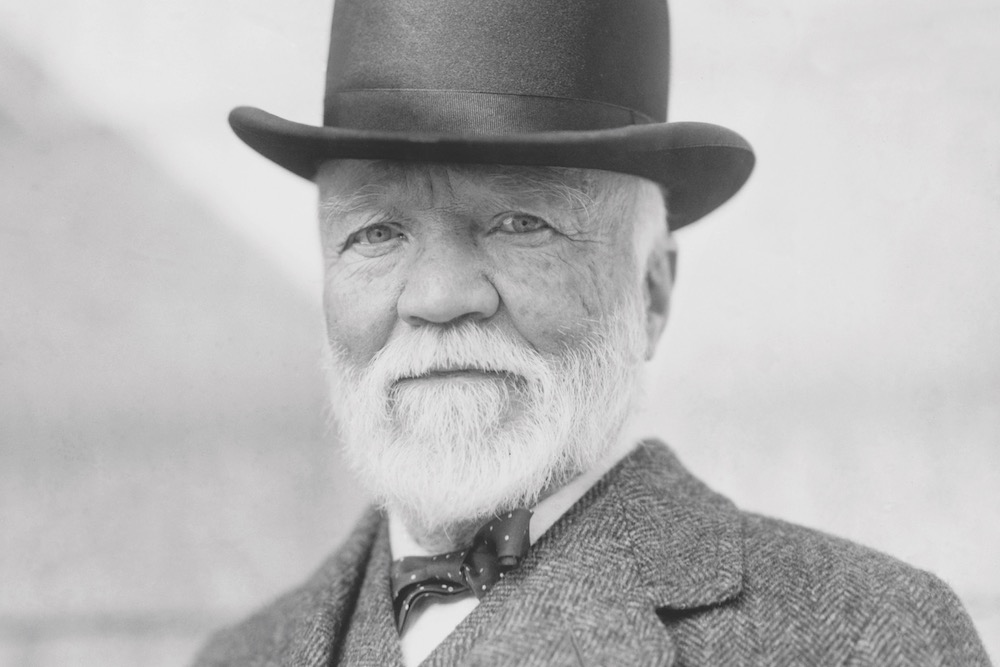

Andrew Carnegie: Respected Genius or Selfish Industrialist?

While wrestling with the complicated legacy of Andrew Carnegie, you may find that he contained multitudes.

Considering he arrived in Allegheny City in 1848 — at the age of 12 — you’d expect Andrew Carnegie’s name to first appear in Pittsburgh’s newspapers decades later, when he was a railroad man. Instead, the city met him on Nov. 2, 1849. A blurb in the Pittsburgh Daily Gazette informed the city that “A messenger boy of the name of Andrew Carnegie … yesterday found a draft for the amount of five hundred dollars. Like an honest fellow, he promptly made known the fact, and deposited the paper in good hands.”

An honest fellow, indeed! The 13-year-old Carnegie could have absconded with $500 and helped his struggling family, which had escaped destitution in Scotland. Instead, he did the right thing, an early indication of his strong moral character. Bravo!

But, as Carnegie biographer David Nasaw pointed out, the draft was worthless without identification. Kind of like if you tried to deposit a check you found on the street, only for the bank teller to say, “Sir, this is made out to Giant Eagle.” What on its surface is a story of an honest boy is actually an early indicator of Andrew’s future as an opportunist who knew how to maneuver himself into a position of public respectability, even if the full truth had harsher lines.

So it goes with Andrew — and our relationship with his legacy. He is either loved or hated. Revered for his “genius” or despised for his “selfishness.” To blame for it all, or merely the absent money man to industrialist Henry Clay Frick’s despotic rule. Worthy of the murals and statues, or deserving of erasure.

My therapist used to remind me of something today’s society has mostly forgotten: “Multiple things can be true.” Andrew Carnegie contained multitudes.

In a note to himself, written while he already was quite wealthy at age 33, Carnegie opined, “The amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry. No idol more debasing than the worship of money.” Publicly, however, he wrote in 1889, “Not evil, but good, has come to the race from the accumulation of wealth by those who have the ability and energy that produce it.”

The man who wrote in an 1886 article, “The time approaches, I hope, when it will be impossible in this country to work men 12 hours a day,” seemed to forget that, in 1885, his employees were not permitted to return to the Edgar Thomson Steel Works unless they agreed to an increase in the workday — to 12 hours.

He who wrote, “To expect that one dependent upon his daily wage for the necessaries of life will stand by peaceably and see a new man employed in his stead, is to expect much,”only to consent to his striking employees immediately being replaced by scabs.

He whose correspondence revealed that he was in regular contact with Frick throughout the 1892 Homestead lockout, and had advanced knowledge that Pinkerton guards were being engaged, told The New York Times the following January, of his wish “to bury the past, of which I knew nothing.”

These are truly damning accounts of his words not agreeing with the truth. And so, some argue, we should erase him and no longer look to his legacy as having any worth to modern Pittsburgh.

But there’s a complicating factor worth exploring: his humanity.

Living in the shadow of a literal castle, Andy grew up destitute in a family whose motto was “death to privilege.” He spent his childhood watching his weaver father fail as a provider until the family left their beloved Scotland for Pittsburgh, where young Andy decided early on that he would assimilate, learn and earn. He learned as a bobbin boy, working 12-hour days in a textile mill for low wages. He learned telegraph operation and then the railroad industry before moving onto iron and, finally, a pivot to steel that cemented his path toward Midas-like riches.

He wanted to do better for his mother than his father ever could, even though that meant becoming a capitalist and industrialist — which placed him in opposition to labor. Andrew seemed to wrestle with this moral struggle his entire life; he never fully freed himself from his destitute childhood, spent in part attending labor activists’ meetings with his dear grandfather. How could he reconcile the opposing forces within his soul — labor and social progress versus laissez-faire capitalism and wealth?

He found a convenient answer in a personalized version of Herbert Spencer’s social Darwinism, which theorized that industrialists like Carnegie were granted by evolution the propensity to use their minds to earn wealth and improve society. Here was the magic formula: Carnegie wasn’t wealthy because he was greedy, but because he couldn’t help it. The trick was to use his money for the betterment of those without the same level of evolutionary advancement. It’s a very problematic theory, but it served to alleviate his inner turmoil. He once fretted that continuing to amass wealth would “degrade me beyond hope of permanent recovery.” That fear never fully escaped him, but this theory soothed him that it would be justified if he gave it all away before death.

He didn’t give away all his money out of guilt over Homestead — or the Johnstown Flood. He laid out his plans to leave no legacy wealth in a piece published several years before those deadly events, and he encouraged his wealthy contemporaries to do the same. Essentially, he said, earn all you can because it is the wealthy who are gifted by evolution with the skills to improve the world, inject the economy with capital, and hire the labor — but give it all away before you die so it can continue to help those who would help themselves.

There are those who look at his murals and justifiably wonder if it’s not time to move on from Carnegie’s legacy — but we should also look at what he left behind. We live in a Pittsburgh that would simply not have become what it did without him, from his part in creating the steel capital of America to his part in every bit of science and art that has come out of Carnegie Mellon University. We should acknowledge that every library that has enriched a mind, every piece of art that has enriched a soul and every endowment that still lives and gives are his legacy, too.

Unlike other industrialists, who left vast stores of wealth to their heirs, Andrew Carnegie gave it nearly all away — some $350 million, an astronomical sum in today’s dollars. He loved his money; he fretted for his soul. He took much; he gave much. Multiple things are true.

Don’t worship Andrew Carnegie; don’t toss him into the trash bin of history, either. Acknowledge where you feel he went wrong and his involvement in events that stole lives. Also acknowledge that due to a constant moral struggle, within which his inner “death to privilege” child warred with the rich man who made his dreams of wealth and nobility come true, he chose to give it all away with deliberate intention, believing in his heart he was leaving a legacy of lasting good.

It’s OK to agree that in many ways, he did.

In her column, Virginia Montanez digs deep into local history to find the forgotten secrets of Pittsburgh. Sign up for her email newsletter at: breathingspace.substack.com.