Profile: The Empathetic Educator, Becky Baverso

Becky Baverso teaches her adolescent students about history — and life.

Students’ hands shoot up when Becky Baverso asks them a question.

“Tell me what you see,” the middle school language arts teacher at St. Bede School says as she gestures to a photo on the board depicting a young girl with a large bow in her hair. “What do you notice about the picture?”

“It’s black and white,” one of the eighth-grade students states. “It looks like there’s someone else in the photo,” another says.

Another slide in Baverso’s presentation simply shows a teddy bear. She asks the class to think of a time they accidentally got separated from their parents or something bad happened, a time when they were scared as a child. One student recalls getting lost while on vacation; another remembers when their parents couldn’t find them while shopping.

Baverso gestures to the teddy bear. “How would things have been different if you were alone and you had a teddy bear?” she asks.

It turns out the little girl in the photo is Shulamit Bastacky, who was an infant when Germany invaded her hometown in Lithuania, formerly Poland, during World War II. Her Jewish parents feared for her life as Jewish people around them were herded into a ghetto and murdered in nearby forests. They gave Bastacky to a Polish nun, who hid the infant in a root cellar for three long years.

Bastacky was miraculously reunited with her parents in an orphanage after the war and eventually came to Pittsburgh, where she shared her story with students, including those at St. Bede. She often carried a teddy bear as a comfort object when telling her story. Baverso shows the class the black-and-white photo again, but this time students can see the young Bastacky is standing next to the nun who saved her.

Baverso uses the story of the woman she came to call a friend in part to connect the Holocaust with real people. She’s been doing so for her entire 25 years at St. Bede.

Earlier this year, the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh named her Holocaust Educator of the Year; she’s the first Catholic educator to receive the honor. The annual award was established to recognize and encourage excellence in Holocaust education in the tri-state area. The winner receives $2,000, and their school receives $1,000 to advance Holocaust education in its classrooms.

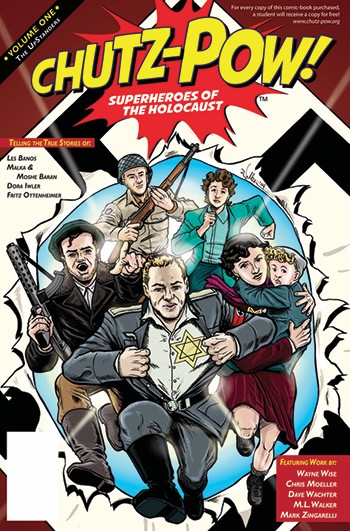

Emily Loeb, the director of programs and education at the Holocaust Center, says Baverso goes above and beyond to bring the Holocaust to life with her students. In her class, students read the “CHUTZ-POW!” comic books, a series the Holocaust Center publishes that’s designed by local artists and writers featuring real-life stories of Holocaust survivors.

“Even though she’s been teaching [the Holocaust] for decades, she is very innovative in her approaches to teaching the curriculum,” Loeb says. “Every year she asks [her students] to create their own podcast, to write their own comic books, to really put themselves in the place of these people, to help them get empathy and understanding of what it would have been like to experience this.”

Loeb says the award goes to teachers who inspire not just students but other educators as well. Baverso is developing a lesson plan around Bastacky’s childhood photo and helped the Holocaust Center to develop a comic book primer for teachers. She’s also attending graduate classes through the National Catholic Center for Holocaust Education at Seton Hill University.

During her lesson, Baverso asks her students what they know about the Catholic Church’s role during the Holocaust. She tells them Hitler targeted priests in Poland and Germany who resisted the German Euthanasia project, and she tells them that the pope at the time was widely criticized for not speaking out publicly against Hitler; however, there is evidence that he encouraged priests and nuns to work in local resistance movements. She asks the students what they think of that.

Some students note nuns like the one who helped Bastacky were able to work underground because the pope did not publicly condemn Hitler. Another says simply: helping people defines what the Catholic Church stands for. Baverso listens to all sides.

“I like these open-ended questions,” the teacher says after her students disperse.

“It’s important that we understand the history … There are a lot of important conversations we can have about their own character development and the choices we make, basic understanding of and acceptance of people’s differences.”

Loeb says the amount the students have learned from Baverso is remarkable.

“It shows how adept she is at not just teaching but teaching this really complex topic to middle school students. And it’s a real special gift.”