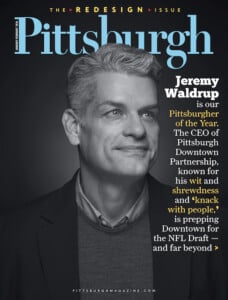

2025 Pittsburgher of the Year: Jeremy Waldrup

Jeremy Waldrup, head of the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, uses wit, shrewdness and a knack with people to revitalize the Golden Triangle.

Jeremy Waldrup has done some outlandish things to entice people back Downtown.

Like the time he bought a $25,000 Heinz pickle balloon, which turned out to be a great idea. Or the time he rented a curling mat and set it up outside an art gallery crawl, which, it turned out, was not such a great idea. (No one wanted to play the niche winter Olympic sport in a gravel parking lot.)

The president and CEO of Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership likes to experiment. He doesn’t mind if people sometimes question his sanity, as they did when he asked his PDP board to not only foot the bill for the ginormous Picklesburgh balloon — but also to insure it. The balloon, known for floating over city streets, has become the emblem of the wildly successful July street fair for 10 years.

His suggestion to erect a 60-foot Ferris wheel atop the Roberto Clemente Bridge drew some funny looks. It was a fun idea, being that inventor George Ferris was a Pittsburgh guy, but county officials wondered if the bridge would collapse. Some $20,000 in engineering reports later, Waldrup became one of the first people to ride the Ferris wheel, now a popular attraction during the annual Oktoberfest, which kicked off two years ago.

You might call that a high point — literally — of Waldrup’s 14-year career in town. The low point was the 2020 pandemic shutdown, when the Golden Triangle ground to a halt, the hum of office workers and traffic suddenly silent, leaving behind people experiencing homelessness, who were camped out in doorways.

More than a decade into his job, Waldrup is working harder than ever to revitalize Downtown, combating complaints that it’s still not safe and that there are too many empty storefronts. PDP is overseeing the renovation of Market Square, doubling the outdoor dining area and adding an open-air steel anchor pavilion and 33 more trees. Waldrup also played a role — along with government leaders, foundations and organizations — in securing $600 million in state-led investment in Downtown. The funding will include modernizing Point State Park and creating the Arts Landing public space in the Cultural District as well as adding hundreds of new housing units to the Golden Triangle.

For his leadership, creative thinking and vision, Pittsburgh Magazine has selected Jeremy Waldrup as its 2025 Pittsburgher of the Year.

“There is no one who is more critical to the success of Pittsburgh than Jeremy Waldrup,” says Herky Pollock, the real estate developer, broker and entrepreneur who moved from the East End to Downtown during the pandemic. “He has been the fabric and glue that has kept Downtown together.”

“I never met a person who didn’t like Jeremy,” he says. “He’s very easygoing and kind of ‘aw shucks,’ but he’s very smart and very shrewd and gets everything done.”

Related: Celebrating our Previous Pittsburghers of the Year

A Beacon for Downtown

On a sunny day in early November, backhoes dig into the concrete of Market Square while office workers maneuver around the obstacle course of orange fencing.

Some passersby look confused, but Waldrup seems at home. He chats up merchants, grabs his regular coffee order at the 106-year-old Nicholas Coffee & Tea Co., and greets the mail carrier. When he walks by The Original Oyster House, co-owner Renee Grippo, known as Mama G, yells out “Jeremy!” She hugs him and he compliments her on the winter cutouts in the window. Her daughter and co-owner, Jennifer Grippo, comes out to greet him. They talk about him making a point to come to their 155th anniversary party fresh from Oktoberfest in his lederhosen.

Waldrup, 50, has pale blue eyes that peer out of Kent Clark-style glasses, a thick wave of gray hair sweeping across his forehead.

He stops to get updates from the construction crew that’s busy working on a new Market Square in time for the NFL Draft, scheduled for April 23-25 and likely drawing some 700,000 visitors to the city. “It will be like a European plaza, pedestrian-first,” he says.

Though PDP is a nonprofit community-development organization created to enhance Downtown, this is the first time the group has overseen a construction project — and it’s a big one, at $15 million. Waldrup has learned the intricacies of the permitting process and the logistics of supporting the operations of local businesses, from accommodating food delivery drivers and customer access to delivering hundreds of pounds of ingredients to restaurants, all with barricades all around them.

He talks to Mike Schoeneman, superintendent at Mascaro Construction Co., about shifting traffic patterns from the south part of the square near PPG to the now completed north side of the square. They discuss the route pedestrians will take for the Block Party that was planned later in the month to mark the halfway point of the revitalization project.

“It will be ready, right?” Waldrup asks playfully.

Schoeneman nods. The Saturday night Block Party was a reminder that dozens of Market Square businesses are still there amid the chaos of construction that has depressed sales during the all-important holiday shopping season. The PDP planned weekly family-friendly events, dubbed the Yinzer Wonderland, in Market Square during the holiday season. Waldrup’s team also coordinated November Light Up Night, when thousands converged on the Golden Triangle to watch the tree lighting.

Making his way to the eastern corner of Market Square, Waldrup passes a haggard-looking man sitting on the sidewalk, wrapped in a plaid blanket. A young woman hands him a sandwich.

Scenes like this have become more visible after the COVID-19 shutdown.

“What makes Downtown feel safer is people. If they are not in here, you are in a cavernous place and you feel like, ‘If I yell, [there is no one to help.]’”

Waldrup says 65% to 75% of workers have returned to Downtown’s offices. But the pandemic showed that the city was overdependent on office space and had too little residential space — something he hopes to change.

Downtown crime became a hot topic and generated headlines, particularly after some highly publicized attacks on bystanders, including an 18-year-old intern who was assaulted by a stranger in the summer of 2024 and a 65-year-old man who was stabbed on the street in 2025. Some merchants left town as safety concerns grew. Robert Fragasso, chairman of the board of Fragasso Financial Advisors Inc., had been working Downtown for 50 years before leaving in 2023. He says his building on the corner of Smithfield Street and Sixth Avenue was at the epicenter of crime, a few doors down from a no-barrier homeless shelter that has since closed.

“We had drug dealers parked in front of our building, dealing. Police were prevented from policing that activity. Drug dealers were preying on the poor homeless people. Our building custodian was cleaning up feces and squirting urine off our sidewalk every morning. We had shootings, fights, overdoses all the time. Our clients told us, ‘We are not coming down.’ … It was like wading through a crime scene of a movie every day. It was untenable.”

He says he was frustrated when he called former Mayor Ed Gainey’s office about the lack of enforcement and social services for those in need. “There was a complete absence of participation. The police expressed frustration to me,” he says.

For all his complaints about the outgoing mayor, Fragasso praised Waldrup for doing all he could through his nonprofit. “Jeremy is a beacon,” he says.

Fragasso also says police began making arrests, and Downtown has improved — but not as much as it should. Merchants say a new police substation that opened on Wood Street two years ago has helped combat crime.

Gainey calls claims that he directed police not to make arrests Downtown categorically untrue, adding that data shows crime in the city decreased under his administration. He noted he thanked officers, PDP, PNC and other partners for their work in improving the city’s “living room” during a press conference held at the Downtown Police Substation in 2025.

“Specifically for Downtown, we held quarterly meetings with corporate leaders, business owners and other stakeholder organizations over the course of two years to provide a forum for open and honest dialogue about the challenges and opportunities for partnership to address those same challenges,” Gainey said in a statement. “While those were difficult conversations, no one was ignored. These discussions were critical in informing the work that ultimately led to the $600 million comprehensive reinvestment plan for Downtown.”

For all the publicity about unsafe streets, Waldrup says, “crimes against people who don’t know each other are very uncommon Downtown.”

PDP also stepped up its efforts to clean up and connect with people. In their bright gold uniforms, the On-Street Services Team picks up trash, removes graffiti and power-washes sidewalks and alleys. The outreach team interacts with the homeless and panhandlers in a nonjudgmental way and connects them with social services.

“I don’t think anybody really wants to sleep on the street. So we have this day in, day out engagement, to get this person into stable housing,” Waldrup says.

Pollock, the real estate developer, refutes the narrative that Downtown is dangerous. “The people who are most critical of Downtown Pittsburgh are the people who live in the suburbs and never come Downtown,” he says.

Service of Others

The guy who is now known for revitalizing cities grew up in tiny Fletcher, North Carolina, population 8,320, on the outskirts of Asheville. An only child, Waldrup worked one summer at age 14 at the local trail riding stable in exchange for a horse.

His father, Chuck, was a police officer turned Pentecostal preacher, and his mother, Libby, led the prayer worship team at the church. The two had met in a Southern gospel touring band — he played drums and she sang — and appeared on the “PTL Club,” Jim and Tammy Faye Baker’s Christian TV show.

As a teenager, Waldrup helped with the children’s ministry at their church. He inherited his mother’s singing voice, crooning the national anthem at high school football and basketball games and performing a solo at his graduation. Though no longer active in the Pentecostal church, he says, “I grew up in the service of others, and I do feel like this job is similar. You are sharing people’s happiness when things are good and you are there for the not-so-great issues with construction or public safety.”

Even as a kid playing Little League, he had a way of defusing conflict among players if things got tense, Chuck Waldrup says. “In the South, we call it unruffling feathers. He would be a jokester and get everyone laughing and calm things down.”

Yearning to attend college in a city, he chose to get his bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Many of his classmates went into banking, but he knew that wasn’t for him. Intrigued by a city development organization called Charlotte Center City Partners, the 21-year-old walked in and asked if he could volunteer.

“They looked at me like I had three heads,” he recalls. No one had ever asked to volunteer before.

He was sent out into the streets with a push cart to hand out pamphlets and field questions about local attractions.

Rob Walsh, then the CEO of the organization, knew immediately that “he was someone special. He had this knack with people.” That summer gig led to a full-time job in economic development. After Waldrup received a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Colorado, Walsh, his old boss — who had become NYC Commissioner of Small Business Services under Mayor Mike Bloomberg — offered him a big opportunity. Waldrup was hired by the South Bronx Overall Economic Development Corp.

At first, New Yorkers rolled their eyes at the young hire. “They counted his niceness against him. They underestimated him,” Walsh says.

Waldrup then became assistant commissioner of district development for the Department of Small Business Services, overseeing 64 Business Improvement Districts.

As he moved up the ladder, the kid who could calm down his Little League teammates proved that he could work with the heads of Business Improvement Districts. “They had egos the size of Arkansas,” Walsh says “They thought, ‘Who was this kid who didn’t grow up in New York telling us what the rules are going to be? How dare you?’ But he managed to do it all with grace and professionalism.”

He was only 35 when he was recruited to PDP, moving to Pittsburgh with his wife, Wesley — a psychotherapist and owner of a private practice in the city’s East End — and their three kids, the youngest just an infant. Waldrup figured since he was heading up the Downtown group, he would live Downtown. Then the couple found out there were hardly any young kids around, and the closest playground was on the North Side.

The family moved to Shadyside and then bought a house in Friendship; they managed with one car until the pandemic, relying often on public transit, Wesley says. Weather permitting, Waldrup commutes via ride-share bike Downtown.

The nonprofit has garnered national attention for Picklesburgh. Waldrup had seen another group, Riverlife, unveil Pierogi Fest, and wished he had thought of the idea based on the energy it created around something so authentically Pittsburgh. He told his staff at a meeting 11 years ago that he wanted to come up with something similar. Russell Howard, the PDP’s former vice president of special events and development, suggested an event centered on the lowly pickle. The marketing director christened it Picklesburgh.

“I knew it was a good idea,” Waldrup says. “I didn’t know it was a great idea.” That became apparent when they ran out of T-shirts the first night of the 2015 festival and had to ask the printer to do an overnight rush order. Four times, USA Today has named it the No. 1 Specialty Food Festival in the country, including in 2025.

Waldrup himself judges the pickle-juice slurping contest. “It can get contentious. You have several thousand people who also watch it with you and have very strong opinions. So thank God for video playback.”

While festivals like Picklesburgh, Oktoberfest and the Holiday Market have given PDP the most attention, Waldrup is proudest of how he reacted to the dire needs of restaurants during the pandemic shutdown. His organization paid for restaurants to create nourishing meals and provide them to people in need.

Now he is looking ahead to rebuilding the city after the trauma of the pandemic, including bringing in more shops and services. “We want to double the residential population in the next 10 years,” he says, which would bring the current 7,300 residents to about 15,000.

To do that, he says, he wants the next young couple considering a move Downtown to find other young families and parks and playgrounds. He’s excited that the 4-acre Arts Landing will include the city’s first children’s playground Downtown.

He adds the NFL Draft is a catalyst and a deadline to improve public spaces.

“We are getting ready to welcome several hundreds of thousands people, and millions will watch this on TV. We want that B-roll shot of Downtown Pittsburgh to show the vibrancy and beautiful architecture and amazing public spaces. But our real focus is on what’s happening beyond the draft.”